Tristerix penduliflorus: Photo by J.R. Kuethe, https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/341912303, CC BY-NC

Tristerix longibracteatus: Photo by Joey Santore, https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/613341336, CC BY-NC

Tristerix verticillatus: Photo by Thibaud Aronson, https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/354120186, CC BY-SA

Tristerix secundus: Photo by sussandro, https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/124997156, CC BY-NC

Tristerix属は13種からなり、アルゼンチン、チリ、ボリビア、ペルー、エクアドル、コロンビアに自生する(POWO)。鮮やかな赤色の花弁を形成し、花序の末端に1個の花を付ける(monad)、子葉が種子から外に出ず、種子内で胚乳から栄養を得るなどの特徴を共有している(Kuijt and Hansen, 2014)。

Tristerix comprises 13 species and is native to Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia (POWO). It shares several characteristic features, including the formation of conspicuous bright red petals, the presence of a single terminal flower in the inflorescence (monad), and cotyledons that do not emerge from the seed but instead obtain nutrients from the endosperm within the seed (Kuijt and Hansen, 2014).

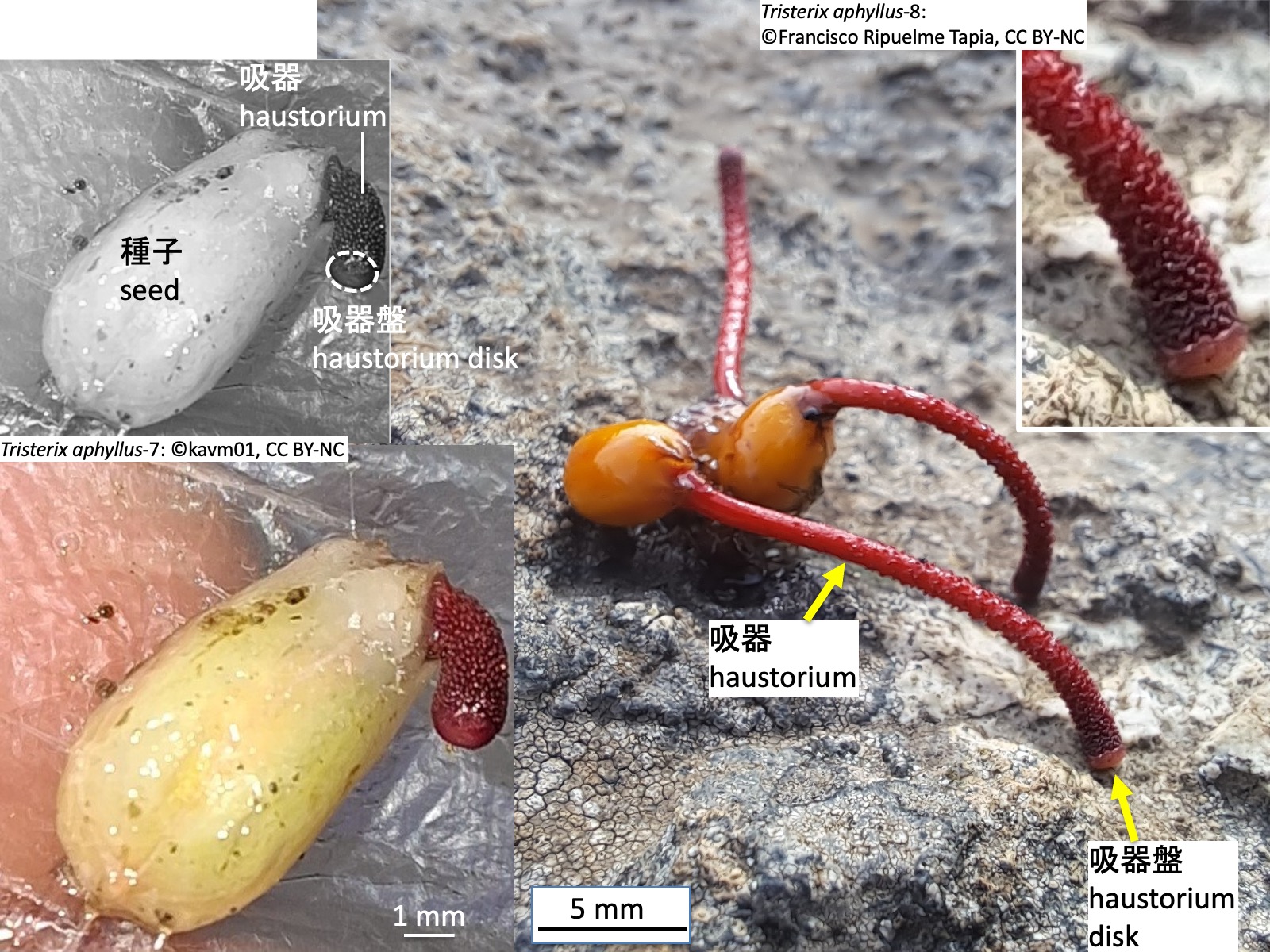

Tristerix属の種は寄生性で、根を形成せず、吸器 (haustorium) を寄主の体内へ伸長させ、寄主から水分や栄養分を吸収する(Kuijt 1988)。種子は粘着質の物質で覆われており、鳥の糞として排出された後、樹皮に接着する。種子内には胚乳があり、癒合した子葉は種子から外に出ず、種子内で胚乳から栄養を得る。発芽に際しては、種子から吸器が伸長する。吸器の先端は吸器盤 (haustorium disk) となり、寄主組織に密着し、組織を破壊して内部へ伸長する。吸器は胚軸が変形したもの(Bhatnagar and Johri 1983)、あるいは、背軸と根のモザイク(Teixeira-Costa 2021)だと考えられている。

Species of Tristerix are parasitic and do not form roots. Instead, they develop a haustorium that grows into the host tissues, from which they absorb water and nutrients (Kuijt 1988). The seeds are covered with a sticky substance, and after being excreted in bird droppings, they adhere to the bark of the host. The seed contains endosperm, and the fused cotyledons do not emerge from the seed but obtain nutrients from the endosperm within the seed. During germination, a haustorium elongates from the seed. The tip of the haustorium forms a haustorial disc, which either closely adheres to the host tissue or penetrates it by breaking down the tissue and then extends internally. The haustorium is hypothesized to be a modified hypocotyl (Bhatnagar and Johri 1983) or root-shoot mosaic (Teixeira-Costa 2021).

Tristerix aphyllus-2: Photo by Jorge Herreros de Lartundo, https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/346919105, CC BY

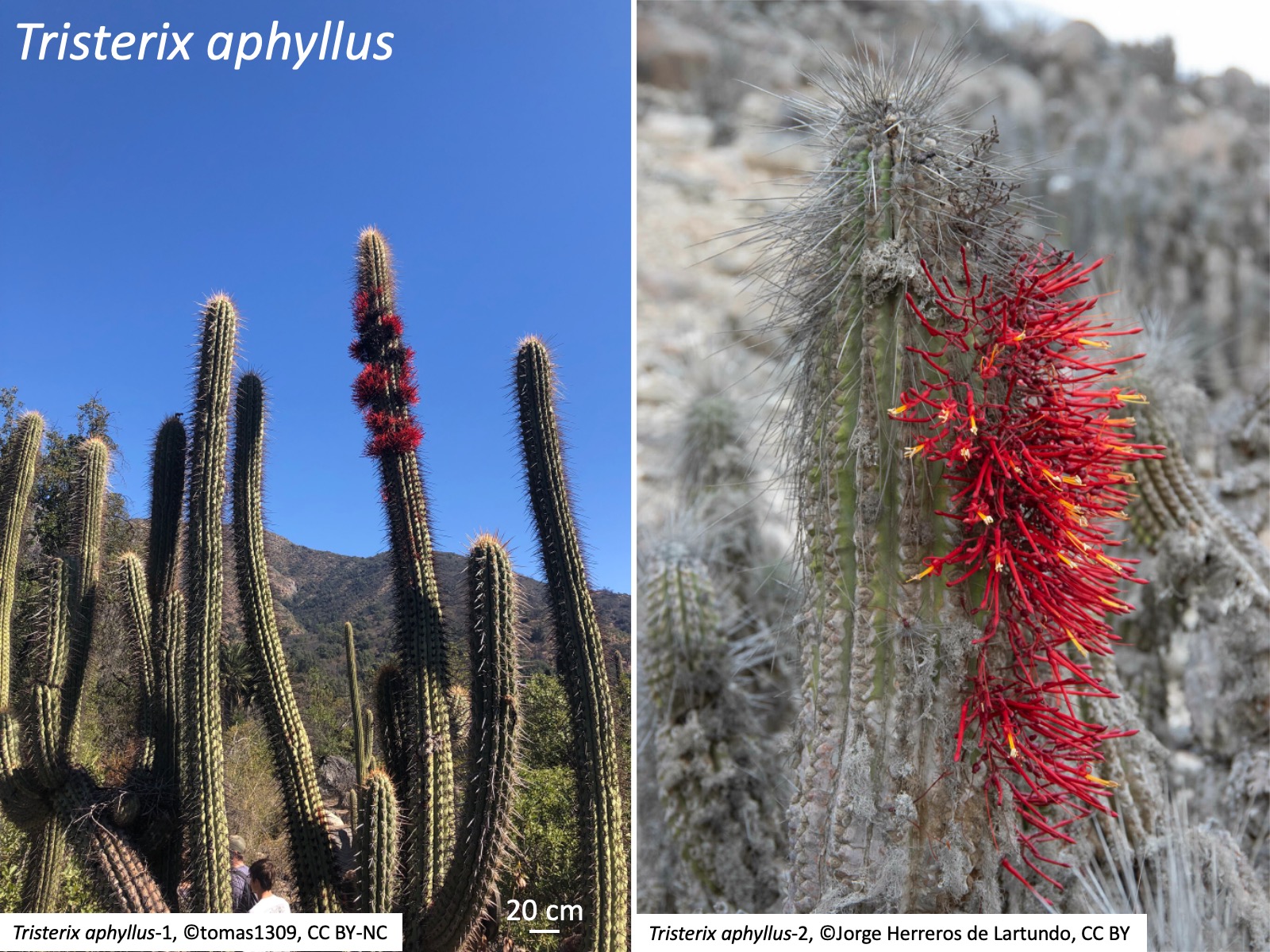

Tristerix aphyllusはチリ中部に分布し(Amico et al. 2007)、姉妹種であるT. corymbosus(Amico et al. 2007)を含む他のTristerix属の種と異なる形態を示す。T. aphyllusを除くTristerix属の種は、光合成可能な葉を付けたシュートを形成する半寄生植物であるのに対し、T. aphyllusは栄養シュートを形成せず葉を形成しない全寄生植物である。

T. aphyllusはサボテン科植物に寄生する唯一の寄生被子植物であり(Ossa et al. 2021)、寄主としてEchinopsis(ex Trichocereus)およびEulychniaが知られている(Mauseth 1990, Amico et al. 2007)。

一般に半寄生植物は、炭水化物を光合成によって自ら生産し、吸器を宿主の導管に接続することで水分と無機塩類を得る(Teixeira-Costa 2021)。一方、全寄生のT. aphyllusでは、吸器が導管に加えて篩管にも接続し、宿主篩管細胞から炭水化物、アミノ酸、脂肪酸などの有機物を得ていると考えられている(Mauseth et al. 1985)。

Tristerix aphyllus occurs in central Chile (Amico et al. 2007) and exhibits a morphology distinct from other species of Tristerix, including its sister species Tristerix corymbosus (Amico et al. 2007). Whereas Tristerix species other than T. aphyllus are hemiparasites that produce shoots bearing photosynthetic leaves, T. aphyllus is a holoparasite that forms no vegetative shoots and bears no leaves.

It is the only angiosperm parasitic plant known to parasitize members of the Cactaceae (Ossa et al. 2021). Echinopsis (ex Trichocereus) and Eulychnia are known as hosts (Mauseth 1990; Amico et al. 2007). In general, hemiparasitic plants produce carbohydrates via photosynthesis and obtain water and inorganic nutrients by connecting their haustoria to the host xylem (Teixeira-Costa 2021). In contrast, in the holoparasite T. aphyllus, the haustorium connects not only to the xylem but also to the phloem, and it is thought to obtain organic compounds such as carbohydrates, amino acids, and fatty acids from host phloem cells (Mauseth et al. 1985).

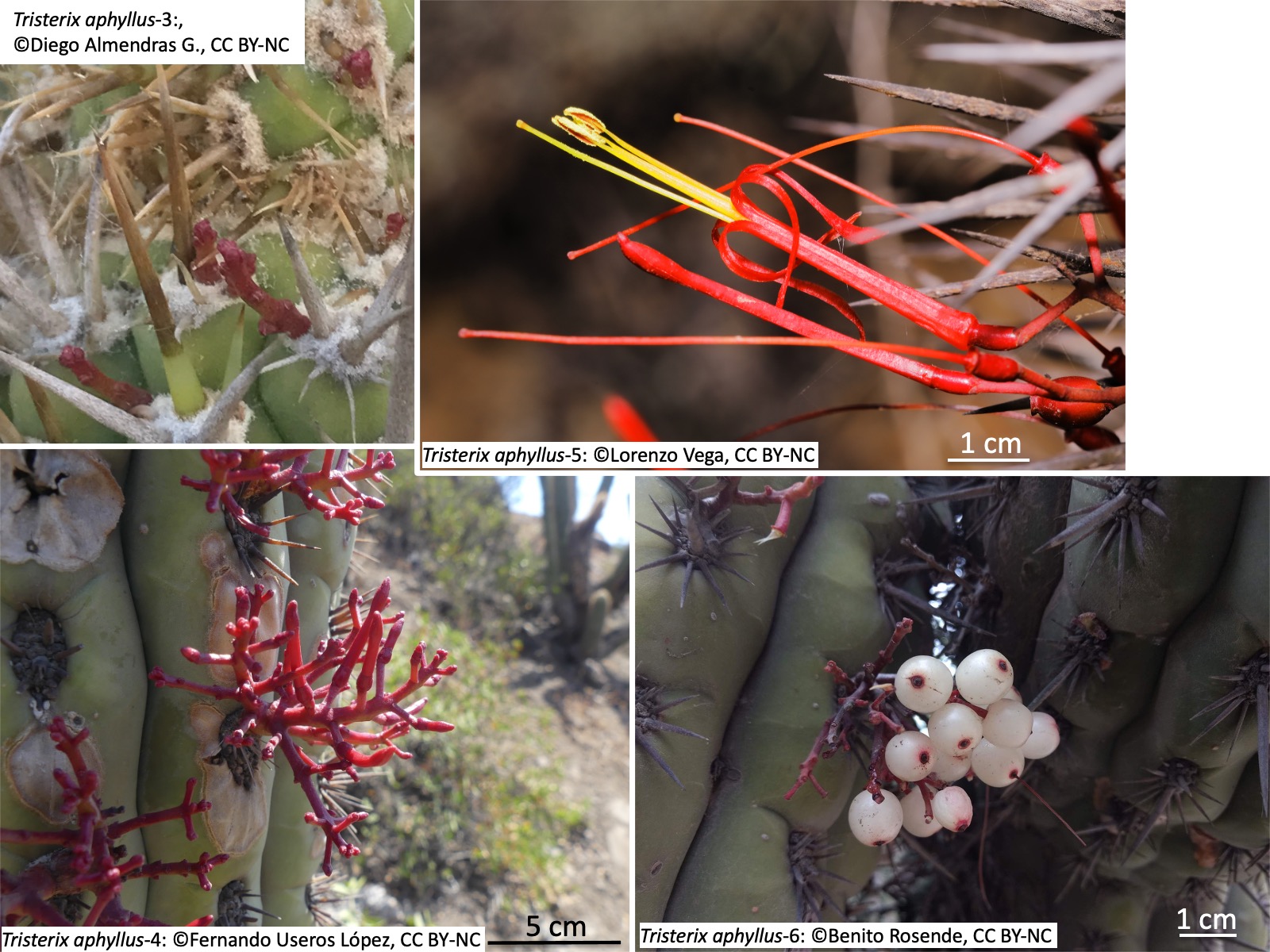

Tristerix aphyllus-4: Photo by Fernando Useros López, https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/172223499, CC BY-NC

Tristerix aphyllus-5: Photo by Lorenzo Vega, https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/113712543, CC BY-NC

Tristerix aphyllus-6: Photo by Benito Rosende, https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/28013312, CC BY-NC

吸器は宿主の柔組織に広がり、花期になると、宿主表面から花序を伸長し(左上写真)、分岐し(左下写真)、開花し(右上写真)、結実する(右下写真)。他のTristerix属の種と同様に、ハチドリ媒花である(Amico et al. 2007)。種子は鳥によって散布される(Amico et al. 2007; Ossa et al. 2021)。種子発芽には果皮 (epicarp) が取り除かれることが必要だが、鳥に摂食され消化される必要はない(Mauseth 1985)。

The haustorium spreads within the host’s parenchymatous tissues. During the flowering season, the inflorescence emerges from the host surface (upper left photo), branches (lower left), flowers (upper right), and sets fruit (lower right). As in other species of Tristerix, it is pollinated by hummingbirds (Amico et al. 2007). Seeds are dispersed by birds (Amico et al. 2007; Ossa et al. 2021). For germination, removal of epicarp is required, but ingestion and digestion by birds are not necessary (Mauseth 1985).

Tristerix aphyllus-8: Photo by Francisco Riquelme Tapia, https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/419928062, CC BY-NC

Tristerix aphyllusの種子も他のTristerix属の種と同様に、子葉が種子の外に出ず、種子内で胚乳から栄養を得る。発芽時には、先端に吸器盤をもつ吸器が伸長する。ただし、T. aphyllusは厚いクチクラ層を持つサボテンに寄生するため、特殊な方法で吸器組織を宿主に侵入させる。

Seeds of Tristerix aphyllus, like those of other species of Tristerix, have cotyledons that do not emerge from the seed but instead obtain nutrients from the endosperm within the seed. At germination, a haustorium bearing a haustorial disc at its tip elongates. However, because T. aphyllus parasitizes cacti with a thick cuticular layer, it invades host tissues using a specialized mode of haustorial penetration.

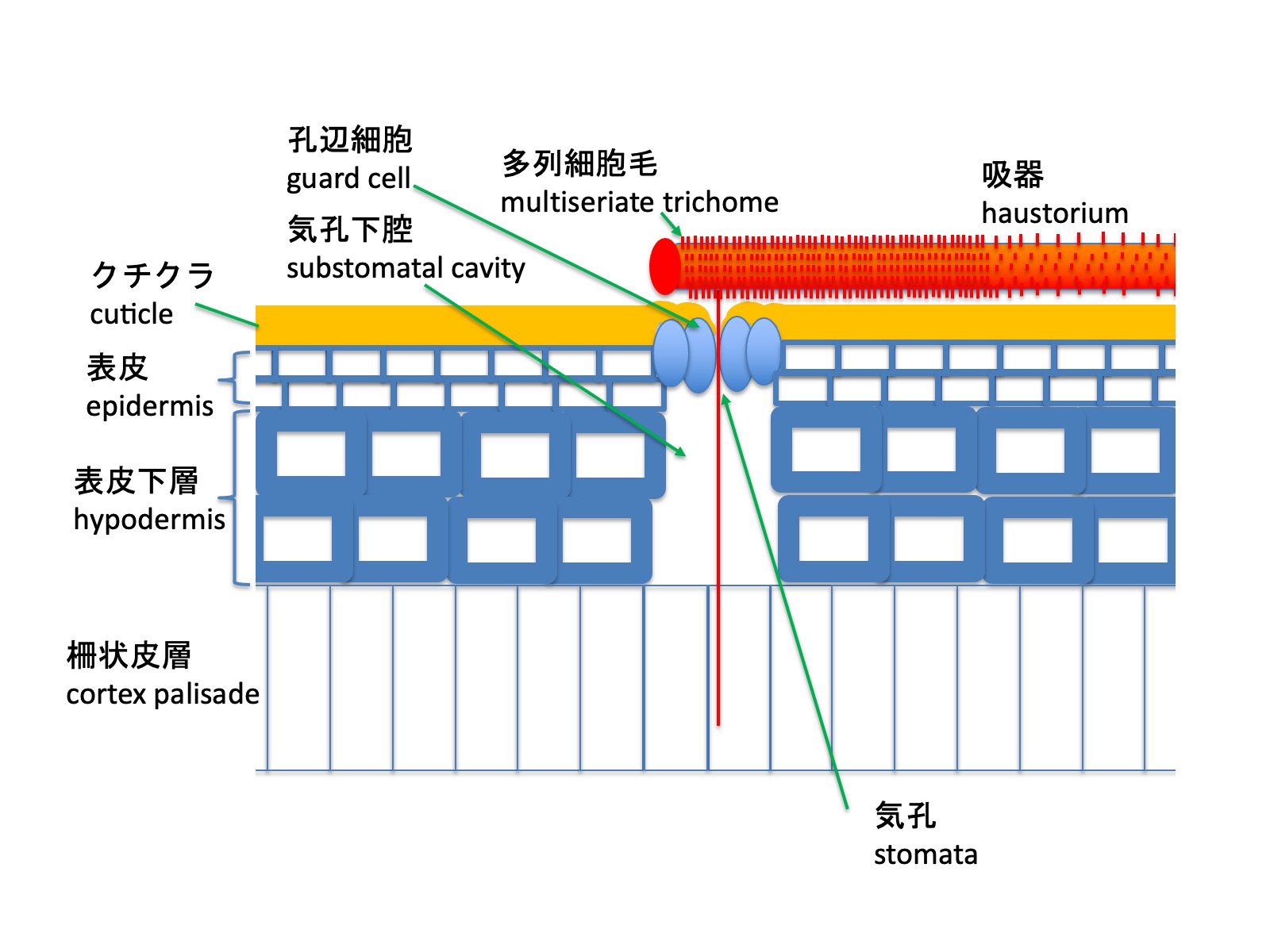

宿主の柱状サボテンのクチクラ(図のオレンジ色の線)は厚いが、気孔のある部分は窪みとなっており、その窪みの下方に気孔が位置する。吸器の表面には数細胞列からなる多列細胞毛が密に形成される。吸器が気孔の上に位置すると、多列細胞毛が気孔へと伸長し、孔辺細胞の開口部を通過する。気孔下腔が存在するため、細胞壁が厚く硬い表皮下層を貫通することなく、柵状皮層へと到達し、その後、柔組織、篩管、導管へと広がる(Mauseth 1985)。多列細胞毛がどのように気孔の位置を認識し、気孔内部へ侵入するのかは明らかになっていない。

人工的にEchinopsis chilensisに播種した場合、17ヶ月後に花序が出現したとの報告がある(Botto-Mahan 2000)。寄生された宿主は、栄養資源を奪われるため、生育が抑制される(Silva and Martínez de Rio 1996)。

The cuticle of the host columnar cactus (shown as the orange line in the figure) is thick; however, regions bearing stomata form depressions, and the stomata are located beneath these depressions. The surface of the haustorium is densely covered with multiseriate trichomes composed of several cell rows. When the haustorium is positioned over a stoma, these multiseriate trichomes elongate toward the stoma and pass through the opening between the guard cells. Because a substomatal cavity is present, the trichomes can reach the palisade cortex without penetrating the thick-walled, rigid hypodermal layer, and subsequently spread into the cortex palisade, cortex, phloem, and xylem (Mauseth 1985). How the multiseriate trichomes recognize the position of stomata and enter the stomatal cavity remains unknown.

When seeds were artificially sown onto Echinopsis chilensis, inflorescences were reported to emerge 17 months after infection (Botto-Mahan 2000). Parasitized hosts exhibit reduced growth due to the loss of nutrients (Silva and Martínez de Rio 1996).

引用文献 References

Amico, G.C., Vidal-Russell, R., and Nickrent, D.L. 2007. Phylogenetic relationships and ecological speciation in the mistletoe Tristerix (Loranthaceae): The influence of pollinators, dispersers, and hosts. Amer. J. Bot. 94: 558–567.

Bhatnagas, R.P. and Johri, B.M. 1983. Embryology of Loranthaceae. In M. Calder and P. Bernhardt eds., The biology of Mistletoes. Academic Press.

Botto-Mahan C, Medel, R., Ginocchio, R., and Montenegro, G. Factors affecting the circular distribution of the leafless mistletoe Tristerix aphyllus (Loranthaceae) on the cactus Echinopsis chilensis. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural. 2000:73:525–531.

Kuijt, J. 1988. Revision of Tristerix (Loranthaceae). Systematic Botany Monographs, Vol. 19. pp. 1-61.

Kuijt, J. and Hansen, B. 2014. The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. Vol. XII. Flowering Plants Eudicots. Santalales, Balanophorales. K Kubitzki, ed., Springer.

Mauseth, J.D., Montenegro, G., and Walckowiak, A. M. 1985. Host infection and flower formation by the parasite Tristerix aphyllus (Loranthaceae). Can. J. Bot. 63: 567-581.

Mauseth, J.D. 1990. Morphogenesis in a highly reduced plant: the encophyte of Tristerix aphyllus (Loranthaceae). Bot. Gaz. 151: 348–353.

Ossa, C.G., Aros-Mualin, D., Mujica, M.I., and Pérez, F. 2021. The physiological effect of a holoparasite over a cactus along an environmental gradient. Front. Plant Sci. 12: 763446.

POWO. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew., https://powo.science.kew.org/, accessed: 6 February 2026.

Silva, A. and Martinez del Rio, C. 1996. Effects of the mistletoe Tristerix aphyllus (Loranthaceae) on the reproduction of its cactus host Echinopsis chilensis. Oikos 75: 437-442. Teixeira-Costa, L. 2021. A living bridge between two enemies: haustorium structure and evolution across parasitic flowering plants. Brazilian J. Bot. 44: 165–178.